Babak Anvari’s Under the Shadow (2016)

Babak Anvari’s debut feature film Under the Shadow (2016) is a spine-chilling allegory of the 1980s Iran-Iraq War, which powerfully adds nuance to the ways women are represented on global screens. Anvari initially faced resistance when he pitched this Farsi-language script, set in Tehran during the War of the Cities – an often-overlooked conflict that shaped the Iranian born British filmmaker’s childhood. However, the film soon won international attention as a feminist horror. It centres on Shideh (Narges Rashidi), a mother left alone when her husband is drafted, caring for her daughter, Dorsa (Avin Manshadi), as their apartment endures missile attacks.

As Shideh experiences femininity, motherhood and war, she begins to realise jinn are tormenting her and her daughter. As a diasporic film rooted in Arabic superstition and produced in Britain, it responds to Iran and the global context. Under the Shadow adds complexity to Iranian depictions of women and motherhood while challenging ideas of the “Other” – often veiled – woman. Anvari engages viewers with transnational gender politics and leaves us questioning where reality ends, and Shideh’s crumbling mindscape begins.

We are introduced to the protagonist, Shideh, as she faces womanhood in post-Revolutionary Iran, an era that saw a purging of Western and non-Islamic influences. In the opening scenes, Shideh sits opposite a university official, under his stern gaze and under the gaze of Ayatollah Khomeini frame on the wall. She pleads to resume her medical studies against an ambiguous allegation of leftist activism. The words “I suggest you find a new goal in life” appear to hit with force like the missiles which inconspicuously rain onto the cityscape outside the window.

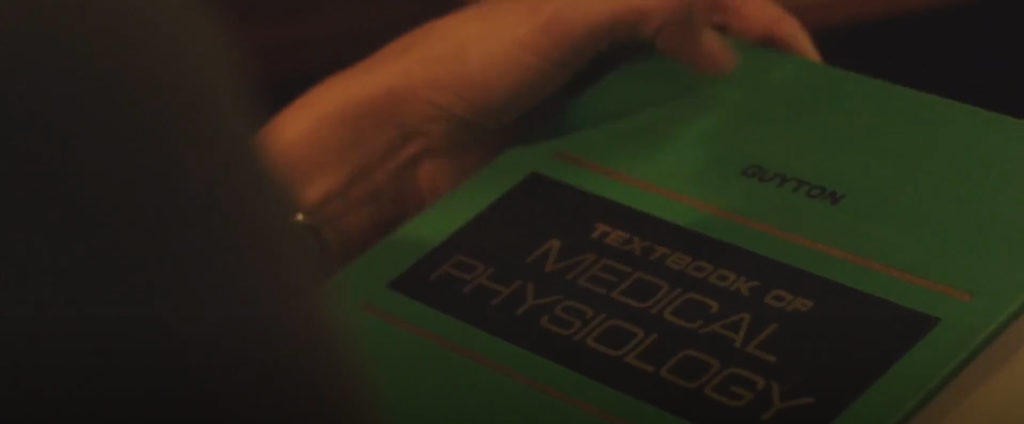

Khosroshahi (2019, p. 7) argues that the backdrop of political turmoil – both in post-Revolutionary Iran and the Iran-Iraq war – brings violence into personal worlds, depicted literally through missiles that leave homes broken apart and scarred. In an early scene, Shideh speaks on the phone to her husband, who is drafted in a conflict zone. The pristine dining room around her stands testament to the domestic duties in which she is trapped, and the room’s ornate emptiness seems almost to suggest it is absurdly waiting to be bombed. Her husband pleads with her to leave the capital for the safety of his family’s house, but she refuses. The apartment and its shelves of old medical textbooks become emblematic of an identity Shideh doesn’t want to leave behind. Her decision to stay seems to be one last opportunity to exercise an agency that has since been taken away from her.

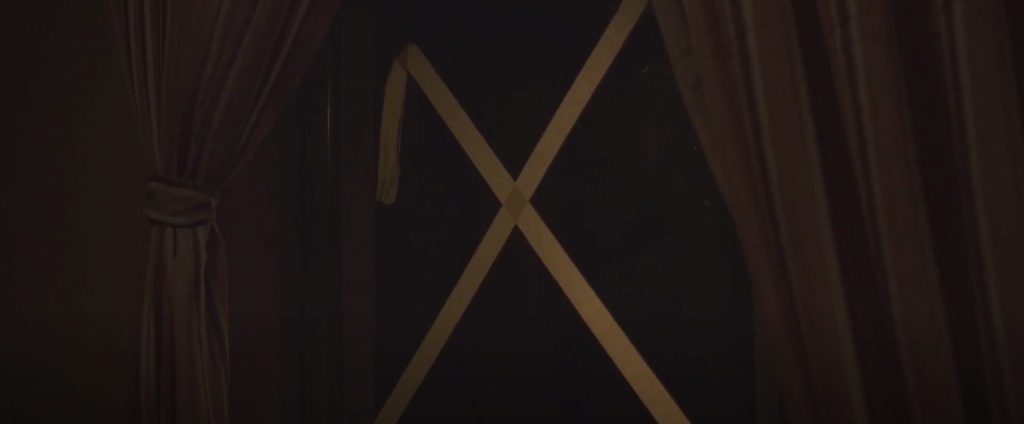

As Shideh speaks on the phone, she stands in the shadow of her taped windows. The motif of Shideh taping up windows escalates to gothic proportions through the film, as she later begins taping crumbling walls. It is as if – Khosroshahi (2019, p. 7) suggests – she is both barring out the dangers of the outside world and barring in herself, and her past identity, as it comes under increasing threat.

Somehow, the terror reaches within the apartment: Shideh’s beloved Jane Fonda workout cassettes appear destroyed in her bin; she cannot find her daughter Dorsa’s cherished doll; a vicious and veiled figure begins to emerge. Director Anvari fittingly employs jinn for their uncontrollable and ambiguous characteristics in Islamic cosmology. In Folklore/Cinema, Peterson (2007, p. 94) explains that jinn occupy a “special, liminal status”, being “of the earth, yet unseen on it”. He continues that “their choice to follow or not follow God is partly a matter of will” (Peterson, 2007, p. 94). Their unpredictability and moral vagueness are characteristics shared with the forces which destroy Shideh’s career aspirations and safety. Like the reasons Shideh was denied a return to university, the jinn’s reasons for haunting her are unclear. Like the missiles which threaten to destroy her home, the jinn pose danger beyond her control. Khosroshahi (2019, p. 7) argues that the jinn becomes a representation of the torment Shideh faces as a woman in post-Revolutionary and worn-torn Iran.

Jinn, Peterson (2007, p. 96) explains, are linked to mental disorders – which becomes increasingly evident in the distortions of reality throughout this psychological horror. In an interview, director Anvari states that the film begins with naturalism, then becomes “freaky and expressionistic” as we enter Shideh’s psyche (Simpson, 2016, para. 19). Cinematographer Kit Fraser eerily reveals the ways trauma distorts reality in scenes capturing Shideh’s sleepless nights. Lying awake under the shadow of a taped window, Shideh impulsively sits up, and the camera follows her line of sight, lurching viewers to a seated position. It then jolts forward, revealing her daughter, Dorsa, standing, staring at her mother in the darkened room. How long has she been there? How did she enter without a sound? Is this Shideh’s dream? The camera seems to know more than we do, and its movements are unnatural and monstrous, as we feel Shideh’s slipping grasp of reality.

Anvari’s paranormal depiction of such a dark time in Iranian history resonates with Cherry’s (2009, p. 167) argument that horror films reflect and address the anxieties of their historical and cultural context. While Under the Shadow is grounded in the Middle East, it was created in the West. Films with such diasporic identities can address different contexts and have layered meanings for different audiences (Cherry, 2009, p. 169). Khosroshahi (2019, pp. 3-4) highlights how these “accented films” can be critical of both their home context (Iran) and host context (Britain). Anvari describes in an interview (Simpson, 2016, para. 21) that “[Iranian] authorities don’t necessarily like films being made outside Iran.” Still, it is made for the Persian community “anywhere in the world”, as well as for the international audience, aiming to introduce them to “a period not many people know about outside of Iran” (Simpson, 2016, para. 21).

The film’s conversations between contexts are visualised when Shideh searches for answers to her haunting experiences through conversations with two neighbours from her apartment block: the pious landlord’s wife, Mrs Ebrahami, and the pragmatic Mrs Fakur. Production designer Nasser Zoubi and set decorator Karim Kheir have powerfully contrasted the mise-en-scène in these two apartments. Mrs Ebrahami’s home is stiff with ornate furniture, absurd spotlessness and framed religious images. Grabbing Shideh’s wrist and explaining her fear of jinn, Mrs Ebrahami, in her full chador, becomes emblematic of traditional and unbending Iranian culture. Peterson (2007, p. 97) argues this representation of jinn – as fearsome and grounded in Islamic culture – reclaims the jinn from their enslavement by Hollywood as “gift-giving genies”. “If they take a personal belonging,” Mrs Ebrahami whispers, “then there’s no escape from them.”

Contrastingly, the mise-en-scène in Mrs Fakur apartment is deshelled and lived-in as the two women walk around unveiled in the comfort of their own home. Frames hold images of loved ones rather than religious iconography and sit on bookshelves. Anvari tells of how he wanted each apartment to have a “unique feel” and “represent the character” (Simpson, 2016, para. 9). As Shideh pages through a book on Mrs Fakur’s shelf about jinn, Fakur becomes the voice of progressive reason and Western influence. “It’s an anthropological book,” Mrs Fakur chastises. “Not a book to find answers in.”

From the film’s uniquely transnational position, Under the Shadow also challenges simplistic depictions of femininity. In a discussion about another film, A Separation (2011), which similarly depicts motherhood in Iran, Shirazi et al. (2015, p. 85) argue these complex modern films “contrast the proliferation of one-dimensional, stereotypical portrayals of motherhood” evident in both Middle Eastern and Western cinema. Khosroshahi (2019, p. 2) argues that Under the Shadow challenges the pure/monstrous dichotomy of the feminine figure.

Throughout the film, the clear divide between Shideh’s pure motherhood and the monstrous jinn becomes less and less apparent, culminating in one of the final scenes where she answers a call from her husband. She stands in their dining room, but it is very unlike the pristine and organised space in the early scenes. Her fall from domestic duties is revealed with a shaking handheld camera. Selective focus shows the carnage of a house pulled apart – books on the floor, a fallen lamp, open drawers, couches pulled apart – as she failed to find her daughter’s doll. In the warm, dim and flickering lighting, it becomes clear that Anvari was effective in wanting to “twist” the safe and comfortable home into “a very threatening place” (Simpson, 2016, para. 24). Over the distressing roar of wind and crackle of static, Shideh’s husband yells, “You’re useless!” He confirms everything she fears: she is unable to pursue the medical career she had once hoped for, she is unable to keep order and safety in her home, and she is unable to protect her daughter. “You can’t look after me, but she can,” Dorsa tells her mum, referencing the jinn. Under the burden of motherhood in post-Revolutionary and war-torn Iran, Shideh faulters from the ideal, pure feminine figure (Khosroshahi, 2019, p. 9). She becomes the monster.

Within the notion of monstrosity explored in Under the Shadow, the veil becomes a complex marker of “Other”, critiquing both the Iranian context and Western assumptions. During the Revolution, veiling was reintroduced as women’s bodies became central to reclaiming Iran’s “lost” Islamic identity (Khosroshahi, 2019, p. 2). Women always had to appear veiled within Iranian cinema, and close-up shots became forbidden (Khosroshahi, 2019, p. 2). Anvari sites these as the reasons he shot the film in Jordan rather than Iran (Simpson, 2016, para. 29).

Shirazi et al. (2015, p. 86) explain the complex ways veiling can represent a character, particularly her class and connection to modernisation. When Shideh attempts to re-enter university in the first scene, she wears a full chador, hoping to portray a conservative identity. Throughout the film, however, she usually wears the roosari (headscarf) and manto (long coat) of a secular/moderate (2015, p. 87) and is often caught under veiling around her apartment block. Within a post-9/11 Western mediascape, which often characterises the veiled woman as oppressed, vilified or victimised, such nuance in costuming adds three-dimensionality to the “Othered” woman (2015, p. 87).

However, Anvari also uses the veil as a motif to leave the audience shivering. The black and white fabric whips around the edges of the screen in the film’s ceaseless, harrowing wind. It causes Shideh to question her reality and causes Dorsa to question her mother. The jinn appears as a consuming veil during the film’s climax, pulling Dorsa away from her. As Shideh rips the fabric, we hear the tearing of flesh and cartilage.The veil becomes an undeniable symbol of the fight Shideh must endure against the post-Revolutionary context for her identity as a mother.

Anvari’s Under the Shadow has begun his directorial career with gasps of fear from London to Tehran. This diasporic horror is as critical of its Iranian context – the overwhelming experience of womanhood amid a Cultural Revolution and war – as it is critical of oversimplified Western attitudes and feminism. This film evocatively diversifies female representation on global screens, leaving viewers’ adrenaline high and minds wide open.

References (APA 9th Edition)

Cherry, B. (2009). Horror and the cultural moment. In Horror (pp. 167-185). Routledge.

Khosroshahi, Z. (2019). Vampires, Jinn and the magical in Iranian Horror Films. Frames Cinema Journal, 1-14.

Peterson, M. A. (2007). Jinn to genies: Intertextuality, media, and the making of global folklore. In S. R. Sherman & M. J. Koven (Eds.), Folklore/cinema: Popular film as vernacular culture (pp. 95-221). Utah State University Press.

Shirazi, M., Duncan, P., & Freehling-Burton, K. (2015). Gender, nation, and belonging: Representing mothers and the maternal in Asghar Farhadi’s A Separation. Atlantis: Critical Studies in Gender, Culture & Social Justice, 37(1), 84-93.

Simpson, P. (2016, December). Under the Shadow: Interview: Babak Anvari. Sci-Fi Bulletin. https://scifibulletin.com/film-reviews/film-interviews/under-the-shadow-interview-babak-anvari/#