A research project by Eve Cogan with the University of Technology Sydney.

Introduction and Research Focus

Recent literature confirms what those working in journalism have recently experienced: the rise of digital media has irreversibly changed the industry. Over 3000 Australian journalism jobs have been lost since 2011 (Dawson et al., 2020), revealing that the business model is under stress. As the industry adjusts, new technologies can undermine the quality of journalism or enhance it.

This research explores how quality journalism can be maintained in the digital age. The Walkley Foundation’s Awards are used as a marker of quality journalism in Australia, being an independently-funded company designed to recognise, elevate and support valuable journalism (The Walkley Foundation, 2022). By comparing the 2002 Walkley Award Winners and the 2021 Winners, this report explains how journalism is evolving and the opportunities journalists have for innovation.

Discussion of Previous Research

A review of recent journalism research shows that the rise of digital media has left news organisations in crisis. This was explored by Dawson and scholars (2020) in their recent and peer-reviewed Longitudinal Study of the Journalism Jobs Crisis. Dawson and scholars used a comprehensive set of 3698 journalist job ads with official employment data from the ABS to highlight how employment remains erratic as the industry searches for a sustainable business model.

Areas of potential for journalism can be seen in Zayani’s (2020) peer-reviewed article on social media and audience engagement. The research could be considered too focused on an anecdotal case study of the Al Jazeera offshoot, AJ+; however, it highlights the importance of creating journalism designed to engage the individual, particularly on social media, rather than blanket broadcasts designed to inform the populace.

Similarly, Burscher and scholars (2017) show how sharing content on social media affects journalism’s traditional role. This research has been cited over 300 times since its release in 2017 and reveals the shift of newsworthiness to the less honoured “shareworthiness”. Newsworthiness and shareworthiness have common characteristics; however, shareworthiness favours human interest and geographical proximity over hard and/or foreign news (Burscher et al., 2017). It is less affected by the legitimacy of claims, which directly impacts the quality of journalism.

Fortunately, research suggests digital media can also invigorate journalism. Garcia-Blanco & Kyriakidou (2021) explore the innovative potential in the future of journalism. The work is too young to have been cited often; however, it confirms a generally accepted trend that multimedia storytelling – such as video, interactive websites or Virtual Reality – allows for deeper audience engagement with stories than traditional modes like text.

New digital technologies like social media can also provoke coverage of issues on the periphery of media biases, such as those of First Nations People. Very recent and relevant work by Ansell and scholars (2021), as well as Nolan & Waller (2021), reference the Walkley winning project by the Guardian on Indigenous deaths in custody, which pivotally relied on social media for its newsgathering and research. The studies also show other First Nations focused social media trends (such as #SOSBLAKAUSTRALIA, #IndigenousDads) which instigated journalistic coverage.

Further study into the specifics of what constitutes quality journalism in today’s digitalised world is vital to maintain the industry’s relevance and provide guidance for innovation. This research will build on existing literature to explore the question: What kinds of storytelling and technology constitute quality journalism today, and how has this evolved from 20 years ago?

Methods

The research method centres on a comparative content analysis of the 2002 Walkley Winners and the 2022 Walkley Winners. The comparisons were conducted through eight-point criteria developed from key journalism studies concepts.

| Criteria | Explanation |

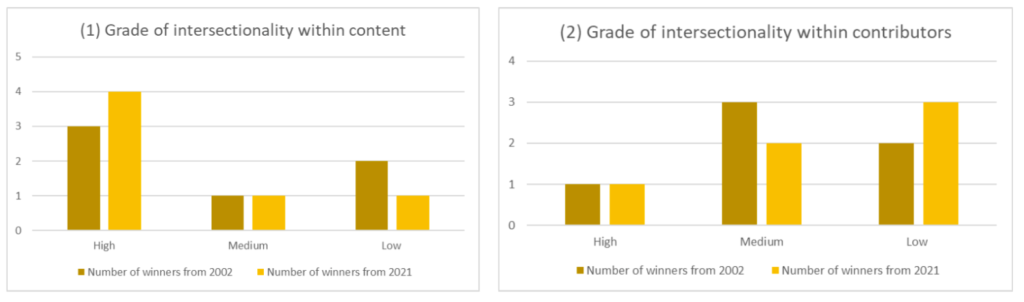

(1) Grade of intersectionality within content (2) Grade of intersectionality within contributors | Criteria 1 and 2 employ Crenshaw’s (1989) framework of intersectionality for understanding how different factors within a person’s identity affect discrimination and privilege. In this way, the study of diversity is embedded as a critical tenant within this research. Stories were analysed for evidence of intersectional topics such as First Nations Australians, LGBTQIA+, female stories, regional issues and racial issues. This criterion was judged on a scale of low (0-1 points of intersectionality), medium (2 points of intersectionality), orhigh (3 or more points of intersectionality). |

| (3) Instigation | Criteria 3 engages with Bruns’ (2009) concept of the “produser” – an audience member who also produces and distributes content in response to their world. Analysis of the Walkley Awards in this criteria considers if the story was provoked by the general news cycle or a people-driven movement such as a protest or social media hashtag. |

| (4) Form | Analysis in this criteria will note how many forms the story is published in. TextAudioVisualMultimedia Form convergence. The final criteria, form convergence, assesses if the story has been told in several ways using different technologies like podcast, video and social media. While there were no examples of this in 2002, many winners in 2021 included not one but several stories, often in different forms. For example, 9’s “Nazis Next Door” won the longer-form video award, then a set of text-based articles on the same topic, also from 9, won the investigative journalism award. This criteria of form convergence draws on Jenkins’ (2014) concept of media convergence, traditionally used to highlight how a shrinking number of conglomerates are gaining control of content production. This is known as corporate convergence, but the concept also applies to content, form and role convergence. |

| (5) Grade of participatory journalism | Criteria 5 draws from Singer’s (2011) concept of participatory journalism, as audiences favour more interaction with journalistic content and become involved in its creation and propagation. This criterion was judged on a scale of Low – designed to be consumed by the populous, or High – designed to engage the individual. |

| (6) Publication value | Criteria 6 draws Burscher et al. (2017) suggestion that the concept of “newsworthiness” has shifted to “shareworthiness”. This criterion considers if the publication value of stories aligned more closely with traditional newsworthiness or shareworthiness (favours human interest and geographical proximity over hard and foreign news and is less affected by the legitimacy of claims). |

| (7) Grade of innovation | Innovation will be assessed on a scale of low, medium or high using Nolan & Waller’s (2021) definition: the story must have created something new and, most importantly, provided public value. |

| (8) Level of outcome | This criteria aligns with Singer’s (2011) concept of participatory journalism. Stories will be assessed on their tangible change-making ability, on a scale of Low – no outcome, only reportingMedium – some outcome, not wholly due to the storyor high – outcome due directly to the story. |

As there are over 30 Walkley Winners in each year, a sample of six comparable categories (labelled A – F) has been used.

| 2002 Award Title | Name | Story |

| (A) Online Journalism | Michelle Feuerlicht | “The Timber Mafia” |

| (B) Coverage of Indigenous Affairs | Tracey Callegari, Julie Nimmo | “No Fixed Address” |

| (C) Coverage of Suburban or Regional Affairs | North to Nowhere Team | “North to Nowhere” |

| (D) Coverage of Sport | Neil Breen | “The Ben Tune Affair” |

| (E) News Report | Michael Southwell | “Investigation: Alcoa Pollution” |

| (F) Gold Walkley/Investigative journalism | Anne Davies and Kate McClymont | “Bulldogs Salary Cap Scandal” |

| 2021 Award Title | Name | Story |

| (A) Innovation | Kylie Boltin, Ella Rubeli, Ravi Vasavan and Emma Anderson | “Ravi and Emma” |

| (B) Coverage of Indigenous Affairs | Karla Grant, Julie Nimmo, Michael Carey, Mark Bannerman and the Living Black Team | “Taken”, “Missing Pieces” and “Heritage Victory” |

| (C) Coverage of Community or Regional Affairs | Andrew Messenger | “‘You feel so powerless’: little room for kids in rural mental health”, “Banksia Mental Health Unit: children’s services ruled not ‘economies of scale’ in plan for new mental health unit” and “Tamworth Banksia Mental Health modelling says New England North West won’t need more general-purpose beds until 2031” |

| (D) Sports Journalism | Michael Warner | “‘Do Better’: The Secret Collingwood Racism Report” |

| (E) Coverage of a Major News Event of Issue/Gold Walkley | Samantha Maiden and the news.com.au team | “Open Secret: The Brittany Higgins story” |

| (F) Investigative Journalism | Nick McKenzie and Joel Tozer | “Nazis Next Door”, “Inside Racism HQ: How home-grown neo-Nazis are plotting a white revolution” and “From kickboxing to Adolf Hitler: the neo-Nazi plan to recruit angry young men” |

Firstly, the criteria were used to analyse the 2002 Walkley Award Winners, case study by case study. This process was repeated for each 2021 winner. Secondly, the data of all the 2002 Walkley Award Winners was compiled and tabulated, with the same being done for the 2021 awards. Third and finally, I compared and contrasted the compiled data from 2002 and 2021 to discuss the evolution of quality journalism and opportunities for innovations.

My research project fits safely within the Research, Integrity & Ethics guidelines documented for FASS students at UTS. The study relies on publicly available data from an ethical organisation and is not engaging with live participants. My research includes insights and terms from recent journalism literature, and all work is clearly cited to acknowledge the academic history I build on.

Research

Walkley Award Winners of 2002 and 2021 Compiled

| (1) Grade of intersectionality within content | Number of winners from 2002 | Number of winners from 2021 |

| High | 3 | 4 |

| Medium | 1 | 1 |

| Low | 2 | 1 |

| (2) Grade of intersectionality within contributors | Number of winners from 2002 | Number of winners from 2021 |

| High | 1 | 1 |

| Medium | 3 | 2 |

| Low | 2 | 3 |

| (3) Instigation | Number of winners from 2002 | Number of winners from 2021 |

| General news cycle | 6 | 5 |

| People/person driven | 0 | 1 |

| (4) Form | Number of winners from 2002 | Number of winners from 2021 |

| Text | 6 | 5 |

| Audio | 2 | 2 |

| Visual | 3 | 5 |

| Multimedia | 3 | 3 |

| Form convergence | 1 | 1 |

| (5) Grade of participatory journalism | Number of winners from 2002 | Number of winners from 2021 |

| Low – designed to inform the populous | 6 | 0 |

| High – designed to engage the individual | 5 | 1 |

| (6) Publication value | Number of winners from 2002 | Number of winners from 2021 |

| Newsworthiness | 5 | 2 |

| Shareworthiness | 1 | 4 |

| (7) Grade of innovation | Number of winners from 2002 | Number of winners from 2021 |

| High | 0 | 2 |

| Medium | 0 | 0 |

| Low | 6 | 4 |

| (8) Level of outcome | Number of winners from 2002 | Number of winners from 2021 |

| High | 2 | 1 |

| Medium | 3 | 4 |

| Low | 1 | 1 |

Discussion of Results

Intersectionality has retained importance in quality Australian journalism over the past 20 years. As Figure 3 highlights, journalism that features high levels of intersectionality performed well in the Walkley Awards in both 2002 and 2021. Despite this, Figure 4 suggests that the intersectionality of the authors is less critical. For example, the 2021 Sports Journalism winner “‘Do Better’: The Secret Collingwood Racism Report” featured highly intersectional content, but its author, Michael Warner, is a straight, white male, has low levels of intersectionality. As stories on the periphery continue to be a vital part of quality journalism, more research into the significance of diverse storytellers is needed.

Figure 5 shows that the last 20 years have seen a significant change in how quality journalism is instigated. All six 2002 Walkley Winners sampled covered stories found within the general news cycle. Contrastingly, most winners in 2021 covered stories that were prompted by people/person driven movements. This grassroots instigation in 2021 tended to come from social media, including “Open Secret: The Brittany Higgins story” and “‘Do Better’: The Secret Collingwood Racism Report” (prompted by Heritier Lumumba). It is clear that new technologies like social media are becoming a vital newsgathering tool for quality journalism.

Technologies newly adopted into quality journalism in 2002 retained their importance in 2021. Figure 6 shows that the forms used over the two years remain very similar. The main points of difference included that the 2002 sample featured more text-based stories, whereas the 2021 winners tended to be more visual. Initially, the criteria included categories for “mobile-centric” and “social media-centric”. While these terms are widely discussed in recent journalism studies, not a single winner from either of the years featured a “mobile-centric” or a “social media-centric” story. The samples’ lack of mobile and social media-centric journalism suggests that these new technologies are yet to progress from novelty projects into mainstream quality journalism.

The design of quality journalism is shifting: blanket broadcasts aimed at informing the population dominated in 2002, but in 2021, winners were creating content directed at engaging individuals. A key example of participatory journalism in 2021 included “Ravi and Emma”, an interactive web story that teaches viewers Auslan using their laptop camera and allows them to pick which perspective of the story they would like to see. Newsmakers should use participatory journalism as defining criterion in their work when aiming for quality in this digital age.

Figure 8 suggests that journalism is experiencing a shift from newsworthiness towards shareworthiness, even within quality journalism celebrated at the Walkley Awards. Shareworthiness (favouring human interest and geographical proximity over hard and foreign news) is the dominant publication value in 2021. Further research is needed to compare the prevalence of shareworthiness in the general Australian news environment versus the Walkley Awards. This research would be significant in revealing if shareworthiness is even more prevalent than this research suggests.

Levels of journalism innovation remained low from the 2002 Walkley Winners to the 2021 Winners. From the sample of both years, only one winner met the definition of innovation as Nolan & Waller (2021) offered, having created something new and, most importantly, provided public value. The single innovative case study was “Ravi and Emma”, an interactive web story that teaches viewers Auslan. Further research is needed into the prevalence of innovation in the general Australian news environment. This research might suggest that journalism innovation is growing but is yet to reach the quality celebrated at the Walkley Awards.

Figure 10 reveals that the levels of outcome evident in quality journalism have remained fairly consistent from 2002 to 2021. An influential work in 2002 included “Bulldogs Salary Cap Scandal” which spurred organisation review and policy updating. This is comparable to the 2021 winner “‘Do Better’: The Secret Collingwood Racism Report”, which had similarly tangible effects on the sporting industry. While some level of outcome is evident in most winners, one might expect higher levels of tangible results in recent journalism with the rise of participatory journalism, which isn’t the case.

Conclusions and Significance

Comparing and contrasting the 2002 and 2021 Walkley Winners reveals how quality journalism is both evolving and stagnating in the digital age. We see a substantial evolution in newsgathering practices as the industry shifts away from the general news cycle towards stories that were prompted by grassroots movements, often on social media. Aligned with this trend, participatory journalism is on the rise. A more significant proportion of 2021 winners created content designed to engage individuals rather than generally inform the masses. The data also suggests an evolution in publication values, as content tends to favour human interest and geographical proximity over hard and foreign news. Even within the quality Walkley Winners, newsworthiness has been replaced by shareworthiness.

A comparison between 2002 and 2021 also shows journalistic stagnation. Intersectional content has remained characteristic of quality journalism during these almost 20 years; however, we are yet to see an increase in the intersectionality of authors. Slow progress is also evident in the multimedia form of winners. While digital technology revolutionised storytelling in 2002, the change hasn’t been exponential, and a similar spread of formats (text, visual, audio) is used in 2021 without much innovation. Generally, levels of innovation and change-making remain similar to 2002, suggesting that cutting-edge journalism forms are not widespread or are yet to gain Walkley acclaim.

Today’s journalists should note the areas of evolution presented in this data (newsgathering with social media, engaging audiences individually, considering shareworthiness) and embed them within their practice to build quality stories. Journalists should also be aware of areas of stagnation in the industry (intersectionality of authors, new forms of digital storytelling, innovation) and consider pushing these boundaries. By highlighting how practitioners can lean into the evolution and lean out of stagnation, this research provides significant guidance for keeping journalism relevant and high quality in the digital age.

References (APA 7th Edition)

Ansell, S., Bradfield, A., Fredericks, B., & Nguyen, J. (2021). Disrupting the colonial algorithm: Indigenous Australia and social media. Media International Australia Incorporating Culture & Policy. 2(1), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/1329878X211038286

Bruns, A. (2011). Gatekeeping, gatewatching, real-time feedback: new challenges for Journalism. Brazilian Journalism Research, 7(2), 117–136. https://doi.org/10.25200/BJR.v7n2.2011.355

Burscher, B., Trilling, D., & Tolochko, P. (2017). From newsworthiness to shareworthiness: How to predict news sharing based on article characteristics. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 94(1), 38–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077699016654682

Dawson, N., Fray, P., Molitorisz, S., & Rizoiu, M. (2020). Layoffs, Inequity and COVID-19: A Longitudinal Study of the Journalism Jobs Crisis in Australia from 2012 to 2020. Cornel ePress. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884921996286

Garcia-Blanco, I., & Kyriakidou, M. (2021). Introduction: Innovations, Transformations and the Future of Journalism. Journalism Practice, 15(6), 723–727. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2021.1935301

Jenkins, H. (2004). The Cultural Logic of Media Convergence. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 7(1), 33–43. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367877904040603

Nolan, D., & Waller, L. (2021). Analysing Innovation in Indigenous News: Deaths Inside. Journalism Studies (London, England), 22(11), 1382–1399. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2021.1944278

The Walkley Foundation. (2022, May 20). About the Walkley Foundation for Journalism. https://www.walkleys.com/about/

Zayani, M. (2021). Digital Journalism, Social Media Platforms, and Audience Engagement: The Case of AJ. Digital Journalism, 9(1), 24–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2020.1816140

As a consumer of the media rather than a creator ; the point than concerns me most is balance. I like to see both sides of an argument equally.

Too often the journalist allows their own bias to colour their reporting. That is opinion not reporting.