The complex system of toilet paper production and consumption is not something most people consider, but it has a monumental impact on our health, wellbeing and environment. The average toilet paper roll uses half a kilo of wood and 140 litres of water (Statista, 2018). What’s more, each Australian uses 88 rolls of toilet paper a year (Statista, 2018). This hygiene staple became even more coveted during pandemic panic buying, which was the most extreme in Australia (Stratton, 2021).

I’ve spent the last two weeks looking into this very niche topic through my university degree, the brand new bachelor of creative intelligence and innovation at UTS. My teammates came from all different faculties (from business to product design and software engineering!) and together, we generated some fascinating insights.

Traditional toilet paper relies heavily on virgin fibre pulp, which contributes massively to deforestation and animal habitat destruction around the world (Stand.earth, 2019). The pulp mills in which these fibres are converted to toilet paper releases chlorine gas and rely heavily on water.

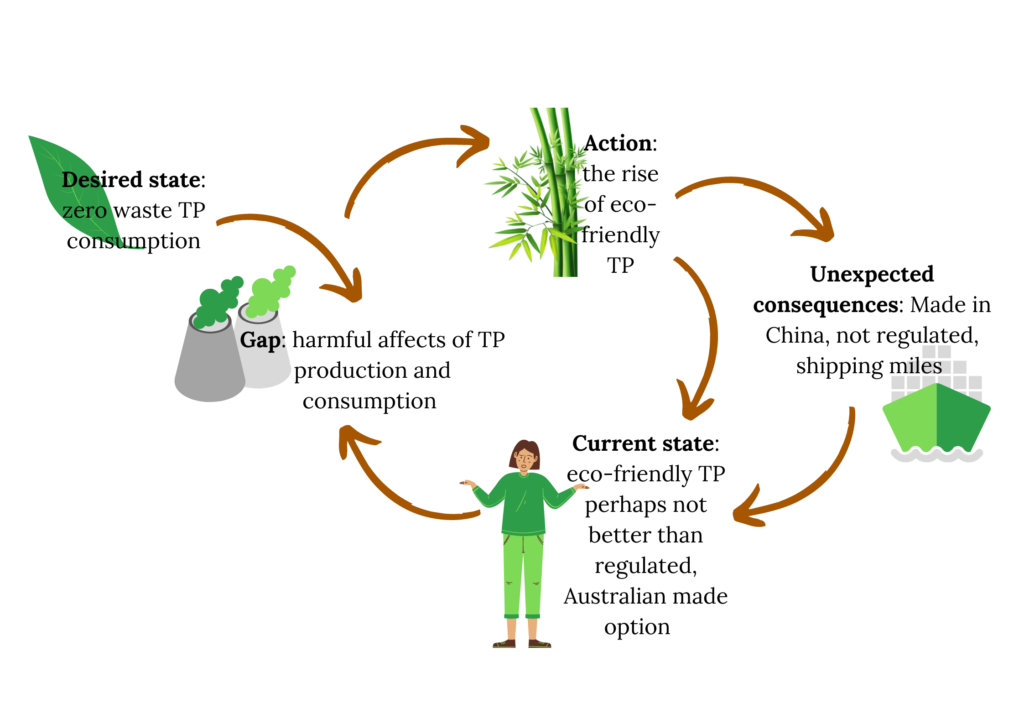

As consumers become more environmentally conscious, alternatives have entered the complex system of toilet paper production and consumption – evident in the rise of ‘eco-friendly’ brands like Tushy and Australia’s own Who Gives a Crap.

These brands specialise in products made from recycled and bamboo fibre pulp. Bamboo is particularly praised for its fast-growing nature and quick biodegradability.

My team discovered a value conflict between companies marketing themselves as eco-friendly alternatives, and ‘standard’ toilet paper manufacturers. Drawing a problem boundary around the Australian market, we compared the ‘premium’ brand Who Gives a Crap against the supermarket favourite Quilton.

The product from Who Gives a Crap has 262 thousand more followers than Quilton on social media, is more expensive and decomposes faster (Who Gives a Crap, 2019). The product is made in China from local materials in local factories and shipped in sea freight around the world. Contrastingly, Quilton is made in Australia and spends more than $10,000 annually on maintaining its Forest Stewardship Council® accreditation (Quilton, 2022) – which Who Gives a Crap has been unable to achieve.

We began to realise the prickly challenge in the toilet paper system lay in the way:

- We define ‘good for the environment’

- We hold companies accountable to this definition, and

- We allow products to be marketed accordingly.

Or, as we realised when we zoomed even further out, perhaps the problem was lying in our cultural preference for paper for toilet hygiene.

We recognised that this complex system needed an intervention, or several if we had any hope of aligning with the ideals for modern life outlined in the Sustainable Development Goals. We hoped to nudge this essential system towards a future that ensures sustainable consumption and production patterns as well as readily available sanitation (Sustainable Development Goals, 2022). Here’s what we came up with:

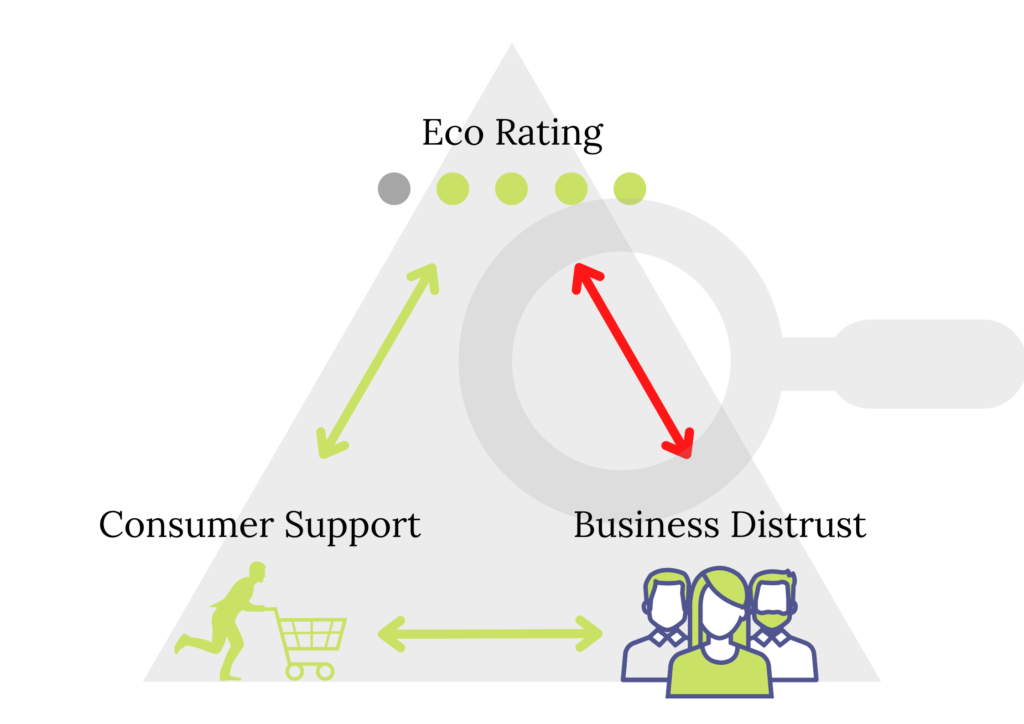

Intervention One: The Eco Rating

Just like the health star rating on food, our first intervention will ensure toilet paper products now have an eco-rating on the packaging which reflects their environmental impacts throughout the product life cycle. Drawing from the fields of business, marketing and science, this rating will be affected by (1) what the pulp is made from, (2) where it’s made, (3) how it’s transported and (4) its end of life biodegradability.

Insights from media and journalism

Marketing and social affirmations have led consumers to assume that an eco-friendly label is an environmentally superior choice. However, when we challenge this dominant framing with clear labelling, we empower consumer choice. As a media producer and journalist, I was drawn to an intervention that uses knowledge to instigate grassroots social change.

Insights about the complex system

Our first safe-to-fail experiment included venturing out to our local supermarket to pop-voxed toilet paper shoppers. The vast majority stated they would swap brands after we outlined the environmental consequences of each brand. Their receptiveness to the idea confirmed the intended consequences of the eco-rating system ‘nudge’.

However, we faced a point of resistance when we emailed toilet paper producers as part of our second safe-to-fail experiment. Rob Little, CEO of the Sydney based toilet paper manufacturer Pacific Tissue, explained his lack of faith in standards that require international audits. He sent us images of factories in China that apparently passed the same stringent auditing as his factory in Australia. By testing our intervention in a real-world context, it became clear that trustworthy international regulations were another complex system attached to the toilet paper problem.

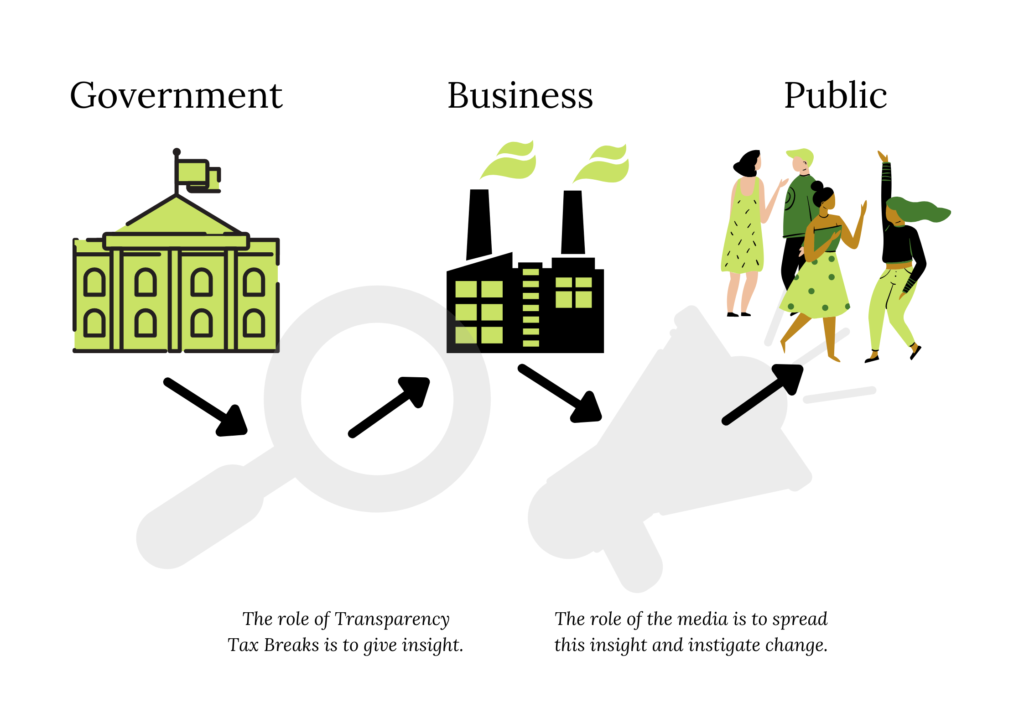

Intervention Two: Transparency Tax Breaks

Transparency Tax Breaks would create a system where the more information businesses make publicly available about the environmental impacts of their products, the lower their tax rate becomes. For example, the more information Who Gives a Crap releases about their financial statements (foreign and domestic), the lower their tax rate becomes. Such information would be significant to both media and consumers.

Insights about the complex system

Transparency Tax Breaks were designed to tackle the uncertainty in the toilet paper production and consumption industry, however, it was difficult to speculate the flow-on effects of this policy without discovering how many businesses would be open to sharing more information, and without knowing what that information would reveal. We sent email probs to 5 major players and heard back from several Australian organisations.

Rob Little, CEO of Pacific Tissue pays over $10,000 a year to keep his Forest Stewardship Council accreditation – the same rigorous accreditation used by Quilton. He lets the auditors spend several weeks in his factory and along his supply lines each year. Little highlights his frustration that, despite his accredited difference from unregulated companies like Who Gives a Crap, he loses customers on a perceived distinction of lacking environmental awareness. These organisations emailed us back and let us know they would be happy to share more information for tax incentives. We received no comment from Who Gives a Crap.

Intervention Three: Bidet

While the two interventions were nudges in the toilet paper production and consumption system, our final invention would flip the system! We would introduce a bidet into community spaces. Bidet or smart toilets are already widely used all throughout Europe and Asia. Their water efficiency and lack of fibre compared to toilet paper would also take the most significant step forward towards a future that ensures sustainable consumption and production patterns as well as readily available sanitation (Sustainable Development Goals, 2022).

Insights about the complex system

Our first safe-to-fail experiment revealed a willingness to swap toilet paper for bidets after individuals were informed about the environmental benefits. Participants in our probes included the BCII cohort and an array of random individuals around Sydney Central Park mall.

However, our more formalised safe-to-fail experiment, which included a gamification initiative, wasn’t well received. We approached the major faculty societies at UTS with a concept for a system in which:

- Bidets are implemented into the UTS buildings as an eco-friendly alternative to toilet paper

- Toilet paper is still available, but it’s consumption is monitored

- Prizes are awarded to the building/faculty based on who uses the least toilet paper e.g. Bar tab covered at an end of year party and the underground

Three of the six societies we reached out to showed resistance to the initiative, claiming it to be too complex or not worth the time. It is clear more of a culture change will be needed before even open-minded young people are willing to participate in bidet culture.

As a media producer and journalist, I find myself positioned as a proliferator of new cultural norms. My role, and the role of those in my industry, is to highlight the benefits of a shift to bidets and then reinforce this culture through the example of public influencers.

Perhaps the toilet paper problem doesn’t need flushing… it needs spraying!

Excellent and interesting research and conclusions.

I swapped to a Bidet many years ago but must confess they are only partially effective! Toilet paper is still required.